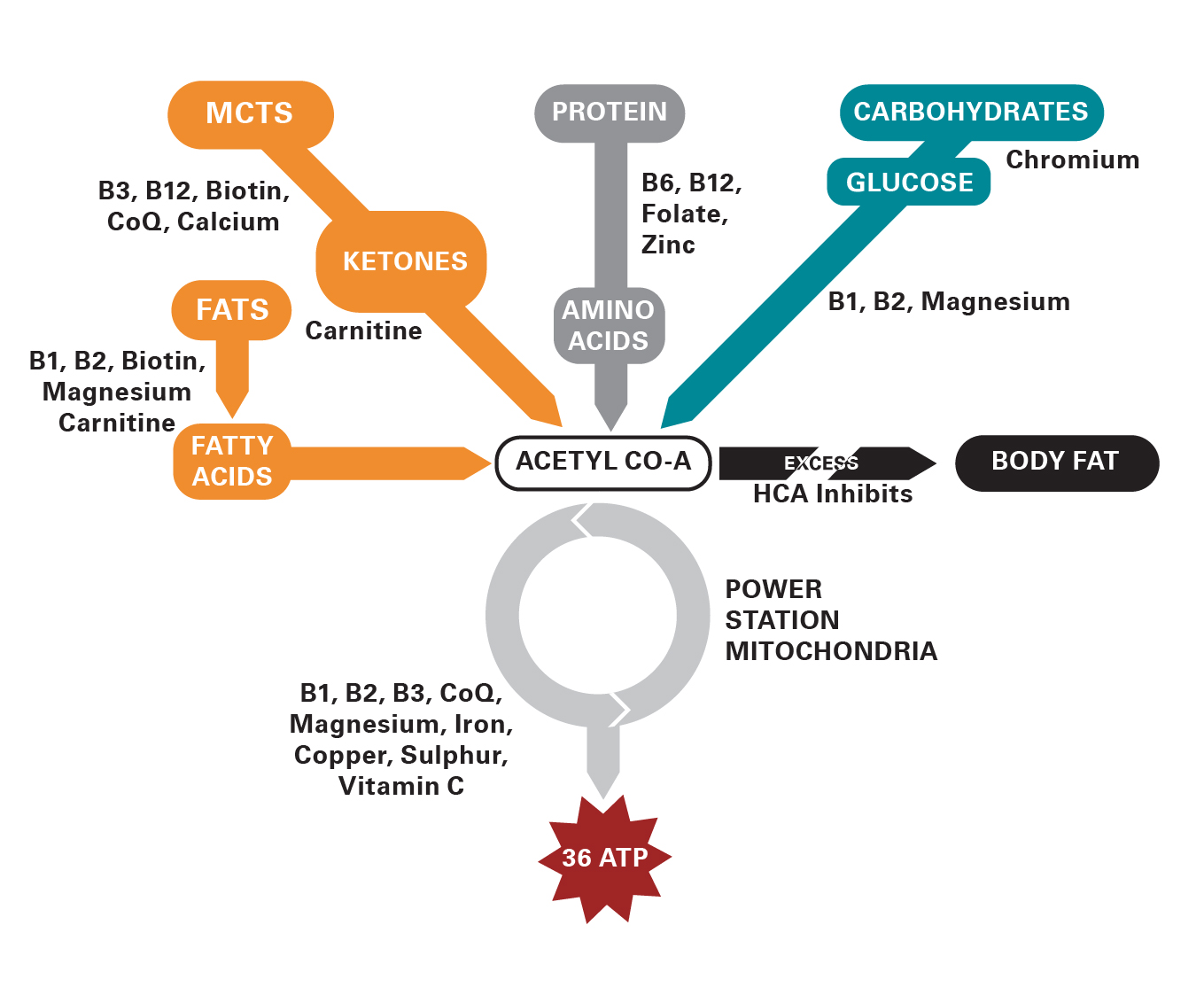

In the figure below you’ll see how we break down carbs into glucose, fatThere are many different types of fats; polyunsaturated, monounsaturated, hydrogenated, saturated and trans fat. The body requires good fats (polyunsaturated and monounsaturated) in order to… into ketones to make the body’s energy called ATP. You’ll also see all the micronutrients that lubricate the whole process. The doors of your metabolismMetabolism is a term that is used to describe the chemical reactions that take place within the body’s cells. The body gets the energy it… won’t open properly without these keys, so they are crucial for good health.

B and C Vitamins: The Energy Nutrients

A quick glance at this figure reveals the importance of a lot of B vitamins, vitamin CWhat it does: Strengthens immune system – fights infections. Makes collagen, keeping bones, skin and joints firm and strong. Antioxidant, detoxifying pollutants and protecting against… and a number of minerals. Many people assume that we get all the nutrients we need from a well-balanced diet. But what is ‘need’? And what is a ‘well-balanced diet’? These vague terms lead to complacency … and deficiency.

By contrast, if you ask a more precise question, such as, ‘What is the optimal intake of vitamin C for optimal health?’ – that is, lots of energy and as little disease as possible – the answer might be anything between 500 and 2,000mg. Even the lower of these two figures is many times higher than the RDA (recommended daily amount; or, as we term it, ridiculous dietary arbitrary!) of 80mg. The ‘average’ person gets just 100mg of vitamin C from their food, which means that a significant minority will get far less.

Theoretically, it may seem like a good idea to optimise your body’s biochemistry, but what difference will it really make? Well, the simple answer is that you will have more energy – both mental and physical – and burn more fat. People with metabolic syndrome shunt energy-rich glucose into storage as fat, but this unhealthy diversion can be minimised and reversed with the right amounts of ‘traffic control’ nutrients. As you can see in the figure , vitamin C is a co-factor in the circular ‘Krebs Cycle’ – a key stage in the energy-making process whether the fuel is glucose or ketones. It is also vital for the manufacture of adrenal and thyroid hormones, both of which instruct the cells to make more energy. Unsurprisingly, then, many studies have linked low levels of vitamin C to increased fatigue. For example, researchers at the University of Alabama Medical Center monitored the vitamin C intake of more than 400 volunteers and asked them to rate their ‘fatigability’. Those who consumed less than 100mg per day had an average score of 0.81. Conversely, those who consumed more than 400mg a day we half as tired, with an average score of just 0.41.1‘Individuals consuming the generally accepted RDA for vitamin C report approximately twice the fatigue symptomatology as those taking about sevenfold the RDA,’ concluded the lead researcher, Dr Emanuel Cheraskin.

One of the knock-on effects of metabolic syndrome – which plays such a key role in the undesirable twenty-first-century cocktail of weight gain, diabetes, heart disease and Alzheimer’s – is a sluggish thyroid. The thyroid produces thyroxine – a hormone that tells the body’s cells to make more energy. If levels of thyroxine start to fall, the brain secretes thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), which tells the thyroid to buck up its ideas! So, high TSH and low thyroxine levels indicate you’ve got a sluggish thyroid gland (a condition that is known as hypothyroidism). Dr William Jubiz, from Cali, Colombia, suspected that this might be reversed by supplementing vitamin C, so he gave thirty-one of his hypothyroid patients an extra 500mg for three months. TSH levels improved in all but one of the participants in the trial, and returned to normal in seventeen of them.2

B vitamins also play vital roles in the energy-making process. However, many people are deficient in at least some of them – most notably vitamin B12 and biotinWhat it does: Particularly important in childhood. Helps your body use essential fats, assisting in promoting healthy skin, hair and nerves. Deficiency Signs: Dry skin,… – especially as they get older. One UK study found that 40 per cent of people over the age of sixty-one have insufficient B12,3 while a recent Irish study reported that only 3 per cent of those aged over fifty have optimal levels4. In part, this may be due to the fact that metformin, the most commonly prescribed diabetes drug, makes B12 harder to absorb. Proton pump inhibitors, such as omeprazole, which the NHS prescribes for millions of people with stomach acid issues at an annual cost of more than £100 million, are even worse in this respect5. In addition to affecting the body’s absorption of B12 and therefore reducing your energy levels, some studies have suggested that these drugs shorten life expectancy6. If you are a poor absorber of B12 – which is only found in animal products, such as meat, fish, eggs and dairy – you will need to supplement literally hundreds of times more than the RDA of 2mcg. When researchers tested how much supplemental B12 was needed to correct even mild deficiency, the answer was more than 500mcg a day!7 It is impossible to eat this amount, so supplementing (or injections) is the only option.

Another crucial B vitamin is niacin (B3), which is converted into nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) – a compound that is responsible for transporting the packets of energy in our food into our cells’ mitochondria. NAD levels decline as we age, but tend to increase when the body is in ketosis, because we need more. Such increases help the body to repair itself during autophagy and improve insulinInsulin is a hormone made by the pancreas. It is responsible for making the body’s cells absorb glucose (sugar) from the blood…. function. Supplementing niacin helps to optimise NAD levels because we need at least 50mg a day (almost three times the RDA). Another important B vitamin – biotin – is often neglected because it can be synthesized in the gut if the right bacteria are present. However, you must ensure that you have sufficient quantities because it is an absolutely vital component in the metabolism of ketones. In addition, deficiency results in damage to mitochondria and DNA as well as accelerated ageing, and you can’t make red blood cells without it. Yet, biotin deficiency is remarkably common: one study estimated that 40 per cent of pregnant women who do not take a multivitamin have insufficient levels.8 Ensure that your multivitamin provides at least 50mcg. Some a ‘high potency’ supplements include biotin and another important nutrient – folate – along with B1, B2, B3, B6, and B12.

Supplementing vitamin C and these B vitamins can make a significant difference to how you feel and your energy levels. One 2011 trial gave a group of volunteers either a multivitamin or a placebo. After twenty-eight days, those taking the supplement exhibited greater physical and mental stamina, better concentration and more alertness than those taking the placebo.9

Co-enzyme Q

Co-enzyme Q (Co-Q) is a crucial ingredient in the final stage of the body’s energy-making process – the electron transport system – because it controls the flow of oxygen, making the whole procedure more efficient. In addition, it boosts the enzyme HMG CoA synthase, which plays a pivotal role in the metabolism of ketones. By contrast, statins suppress this enzyme, which is why their side-effects often include muscle pain and fatigue. In one trial, fifty patients who had been taking statins for two years were taken off the medication after complaining of muscle pain. Their symptoms improved dramatically when they were given Co-Q.10

Co-Q also mops up free radicalsFree radicals are molecules produced when the body breaks down food or by environmental exposure to things like cigarette smoke, pollution and radiation. Free radicals…, which accelerate the ageing process and damage artery walls, among other harmful effects, if left unattended. These dangerous compounds are created during normal metabolism but also when we come into contact with pollution, the sun’s radiation, cigarette smoke and charred, fried food. There is no evidence that supplementing Co-Q has any adverse effects (even when it is taken in very high quantities over a long period of time), while the benefits may be profound. In one study, volunteers who were given 300mg of Co-Q for eight days reported greater energy and demonstrated improved performance during twice-daily, intensive, two-hour physical workouts.11 Many other studies have shown that Co-Q has a positive impact on heart and artery health.12 Therefore, I recommend ongoing supplementation of 30–60mg of Co-Q each day, or 90–120mg if you are taking statins or have been diagnosed with cardiovascular disease. Many different products are available, but I recommend those that are oil soluble, as these are most readily absorbed by the body.

A number of foods contain Co-Q, but not always in the form that our bodies can use. There are ten different types – from Co-Q1 to Co-Q10. Yeast, for example, contains Co-Q6 and Co-Q7. However, only Co-Q10 is found in human tissues, so this is the form that you should supplement. The ‘lower’ forms of Co-Q should not be neglected, because the liver can convert them into Co-Q10, although we seem to lose this ability as we age, which is why supplementation is so important for elderly people. The best dietary sources of Co-Q10 are meat, fish (especially sardines), eggs, spinach, broccoli, alfalfa, potato, soya beans and oil, wheat (especially wheatgerm), rice bran, buckwheat, millet and most beans, nuts and seeds.

The table below gives the amounts of Co-Q10 in a variety of foods.

| Meat | Amount (mg per g) | Amount (mg per g) | |

| Beef | 0.31 | Pork | .024-.041 |

| Chicken | .021 | ||

| Fish | |||

| Sardines | .064 | Mackerel | .043 |

| Flat fish | .005 | ||

| Grains | |||

| Wheatgerm | .0035 | Millet | .0015 |

| Buckwheat | .0013 | Rice bran | .0054 |

| Beans | |||

| Green beans | .0058 | Soya beans | .0029 |

| Aduki beans | 0.002 | Soya oil | .092 |

| Nuts & Seeds | |||

| Peanuts | .027 | Sesame seeds | .023 |

| Walnuts | .019 | ||

| Vegetables | |||

| Spinach | .010 | Broccoli | .008 |

| Peppers | .003 | Carrots | .002 |

Carnitine: Essential for Burning Fat & Ketones

Like Co-Q10, carnitine is known as a ‘semi-essential’ nutrient, which means that your body can make it, but it cannot make enough for optimal health, especially if you are getting on in years. In addition, though, you need more carnitine when you are in ketosis because it plays a key role in both burning fat for energy and feeding fat into the body’s ketogenic furnaces. Therefore, carnitine deficiency is quite common among people on a ketogenic diet. For instance, a study of children with epilepsy who had been following a strict high fat diet found that 17 per cent were carnitine deficient.13

Similarly, deficiency can become a problem when people burn more calories than they eat, even over a relatively short period of time. One study analysed the carnitine levels in a group of soldiers who skied fifty-one kilometres in four days – an extreme test of physical endurance in which the participants burned more than double the calories they were able to consume. The more energy they expended, the more carnitine they needed to transport fatty acids into their cells’ mitochondria for fuel.14 Even when the body is not in ketosis, more than half of the heart’s energy needs are met by burning fat; and, since it has to work hard every second of every day, it demands a steady, constant supply. Carnitine is the delivery boy that carries the fatty acids this vital organ needs. It also removes the toxic by-products that are created when the fuel is burned.

A number of trials suggest that carnitine supplementation can increase ketone levels, which may be a useful tool for dietary fine-tuning. For instance, parents who added carnitine to their epileptic children’s ketogenic regime reported substantial reductions in fits.15

I recommend taking carnitine at least twice a day, because it remains in the body for no more than a few hours. If you want to accelerate your entry into ketosis, I suggest a total of 250–500mg per day. If you are burning ketones – for example, if you are an endurance athlete – take at least 500mg per day, divided into two or more doses. However, you could easily double this, as there no toxicity concerns with supplementing up to 2,000mg a day.

Carnitine is especially helpful if you drink alcohol, have chronic fatigue, engage in endurance sports or suffer from low libido. So, it’s good for your heart, good for your brain, good on the track or ski runs and good for your love life … especially if you plan to be in ketosis for an extended period of time.

Hydroxycitric Acid: The Thai Secret

Thailand, and South-East Asia in general, has some of the lowest rates of obesity, diabetes, cancer and heart disease in the world. In part, this may be due to the prevalence of tamarind fruit in the traditional Thai diet.

There is a compound called hydroxycitric acid (HCA) in the rind of the tamarind that suppresses the key enzyme in the body’s fat storage process (ATP-citrate lyase). This has a significant positive impact on levels of ‘bad’ LDL cholesterolLDL is short for low density lipoprotein. It is the “bad cholesterol” which collects in the walls of blood vessels, causing blockages. High LDL levels… in the blood, fatty liver and inflammation, risk of heart disease and blood sugar issues associated with diabetes.16 It also cranks up activity in the thyroid, which prompts an increase in metabolism, so more fat is burned for energy.17 In one study, rats that were fed HCA lost significant amounts of weight, experienced better blood sugar control and suffered less inflammation.18 It also reduces appetite, possibly by boosting the secretion of serotoninSerotonin is a hormone found naturally in the brain and digestive tract. It is often referred to as the ‘happy hormone’ as it influences mood…..

Moreover, Thomas Seyfried, who has pioneered the use of ketogenic diets in the treatment of brain cancer, believes that HCA may prove to be an important ally in the ongoing battle against glioblastoma. He has reported particularly impressive results when it is combined with alpha-lipoic acid (ALA).19

I recommend supplementing about 2g of HCA per day (e.g. three doses of 750mg) to aid weight loss. A meta-analysis of nine studies of HCA supplementation reported average weight loss of about 1.2kg (2.7lb) in eight weeks20, but participants in trials that gave more than 2g a day fared much better, averaging about 3.5kg over the trial period (roughly 1lb per week). As an example, one team of researchers placed sixty volunteers on a 2,000 calorieCalories are a measure of the amount of energy in food. Knowing how many calories are in the food we eat allows us to balance… diet plus a thirty-minute walking exercise programme and gave them either a placebo or 2,800mg of HCA per day in three equal doses.

After eight weeks, those taking HCA had lost 5.4 per cent more body weight and their BMI was 5.2 per cent lower than the placebo group. In addition, their food intake, total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, triglycerides and serum leptin levels (the hormone that triggers eating) were all significantly lower, while their ‘good’ HDL cholesterolHDL is short for high density lipoprotein. It is the “good cholesterol” responsible for removing harmful cholesterol from the bloodstream. High HDL levels reduce the…, serotonin levels and excretion of urinary fat metabolites (a biomarker of fat oxidation) were all significantly higher. No adverse effects were reported.21 There have been some reports of liver toxicity in other studies, but only among people with diabetes or fatty liver disease, those on potentially liver-toxic medication and/or those who were following extremely low calorie diets. There is no evidence that supplementing HCA causes any harm to people who are in generally good health. Indeed, a major review deemed it safe to use up to 2,800mg a day,22 which, as we have seen, is enough to support weight loss. Even so, I would err on the side of caution if you have any sort of liver dysfunction or non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

For my formulation with Garcinia Cambogia, a natural form of HCA, see GL Support with Carnitine.

Elemental energy

The minerals calciumWhat it does: Promotes a healthy heart, clots blood, promotes healthy nerves, contracts muscles, improves skin, bone and dental health, relieves aching muscles and bones,…, magnesiumWhat it does: Strengthens bones and teeth, promotes healthy muscles by helping them to relax, also important for PMS, important for heart muscles and nervous…, ironWhat it does: As a component of red blood cells, iron transports oxygen and carbon dioxide to and from cells. Also vital for energy production…., chromiumWhat it does: Helps balance blood sugar, normalise hunger and reduce cravings, improves lifespan, helps protect cells, essential for heart function. Deficiency Signs: Excessive or…, zincWhat it does: Component of over 200 enzymes in the body, essential for growth, important for healing, controls hormones, aids ability to cope with stress… and copper are also vital for energy production. The first two are perhaps the most important because all of the body’s muscle cells need an adequate supply of both in order to contract and relax efficiently. Fortunately, most Westerners get more than enough calcium in their diet. However, magnesium deficiency is very common among people who eat insufficient quantities of fruit and vegetables.

Three-quarters of the body’s enzymes need magnesium. It plays a key role in the Krebs energy-making cycle, is vital for carbohydrateCarbohydrates are the primary source of energy for the body as they can be broken down into glucose (sugar) more readily than either protein or… metabolism and helps nerve cells transmit their messages. Symptoms of deficiency include cramp, muscle weakness or tremors, insomnia, nervousness, hyperactivity, depression, confusion, irregular heartbeat, constipation and lack of appetite. The average daily intake in the UK is about 272mg, but we need about 450mg for optimal health. If you are conscientious about eating your greens, and have some nuts and seeds each day, you will probably get about 350mg. Pumpkin seeds are a great source, as are almonds and chia and flax seeds: a small handful provides about 75mg. Nevertheless, it is a good idea to take a daily multivitamin and mineral that gives you at least 100mg of magnesium (plus double that amount of calcium, if you feel you might be deficient). Your body needs zinc, together with vitamin B6, to make the enzymes that digest food.23 These micronutrients are also essential for the production of insulin. A lack of zinc can disrupt appetite control and even diminish the senses of taste and smell, which can result in a preference for meat, cheese and other foods with strong flavours. Zinc is found in nuts and seeds, meat, fish, eggs, beans and lentils. In addition, these foods are good sources of iron, copper and sulphur, which are also key players in the electron transport system. I recommend supplementing 10mg of zinc, 10mg iron and 0.5mg of copper each day. Onions, garlic and eggs all contain plenty of sulphur, so there is no need to supplement it if you eat these foods.

Chromium Reverses Insulin Resistance

The older you are, the less likely you are to be eating enough chromium24. It is an essential mineral that helps stabilise blood sugar by making you more sensitive to insulin,25 thus reversing insulin resistance. Presumably as a consequence, supplementing chromium has been shown to reduce appetite and promote weight loss,26 mitigate mood dips27 and depression,28 and reduce fatigue in diabetics.

The average daily intake of chromium is less than 50mcg, whereas optimal intake, certainly for those with blood sugar problems, is closer to 200mcg. Diabetics need considerably more – about 600mcg – to resensitise their insulin receptors. It has many other benefits, too. A recent study gave a group of volunteers either 600mcg of chromium or a placebo for four months. At the end of the trial, the chromium group had lower blood glucose both before and after meals; their levels of HbA1c (the key long-term blood sugar marker) and cholesterol were both significantly lower, too.30 A meta-analysis of twenty-two previous trials reported similar findings.31 There are two words of caution, however. First, because chromium often boosts energy, it can make sleep difficult if taken in the evening. Therefore, I recommend one tablet with breakfast, one with lunch and one in the afternoon, before 5 p.m. Second, diabetics often find that their blood sugar has stabilised after taking 600mcg of chromium for a few months. At that point, low blood sugar becomes a real possibility, so the dose should be reduced to around 200mcg.

Chromium is found in relatively high concentrations in whole grains, beans, nuts and seeds, and especially asparagus and mushrooms. (By contrast, 98 per cent of the chromium is removed from white flour in the refining process – another good reason to steer clear of refined foods.) However, you are unlikely to achieve optimal intake from diet alone. Therefore, I recommend supplementation, even if you are not diabetic. Chromium polynicotinate is probably the best form to try, as it also contains niacin (vitamin B3). The liver uses these two micronutrients to make a substance called glucose tolerance factor, which, as the name suggests, enhances the body’s ability to deal with glucose by binding to insulin and increasing its efficiency.32

Supplements for Energy

Given that all of these vitamins and minerals boost the body’s energy-making processes and therefore reduce the storage of fat, it is logical to assume that guaranteeing optimal daily amounts through supplementation will aid weight loss. But is this the case?

Well, one study monitored three groups of people, all of whom followed a strict low GL diet: those who took no supplements; those who took a basic multivitamin and mineral, plus vitamin C and essential fats; and those who took these plus at least two of chromium, HCA and 5-HTP (the latter boosts serotonin, which controls appetite). Those on the diet alone lost an average of 550g (1¼lb) per week; those who took the basic supplements lost 680g (1½lb) per week; whereas those who took these and the additional supplements lost 900g (2lb) per week.33

Ensuring an optimal intake of all the nutrients that play a role in turning food into energy is a key part of the energy equation. Therefore, it can accelerate weight loss and reverse metabolic syndrome and related diseases, such as diabetes. Of course, eating the right kind of food is essential, but supplementation is the best way to guarantee that you will achieve these optimal levels every day.

Top Vitamin and Mineral Tips

- Include foods that are rich in B vitamins (fish, green vegetables, beans, lentils, whole grains, mushrooms, eggs) and vitamin C (green vegetables, berries, citrus fruit) in your diet.

- Eat more good sources of the enzyme Co-Q10 (sardines, mackerel, sesame seeds, peanuts, walnuts, beef, pork, chicken, spinach).

- Ensure you get plenty of magnesium (from almonds, chia and pumpkin seeds, green vegetables), calcium (from cheese, almonds, green vegetables, seeds), zinc (from oysters, lamb, nuts, fish, egg yolk, whole grains, almonds, chia seeds) and chromium (from whole grains, beans, nuts, seeds, asparagus, mushrooms).

- Supplement a high potency multivitamin and mineral twice a day to guarantee you get all the B vitamins, magnesium (at least 100mg), zinc (at least 10mg), copper (at least 0.5mg) and iron (at least 10mg) you need. For my formulation see Optimum Nutrition Formula.

- Supplement 500mg to 1g of vitamin C twice a day (no multivitamin contains this much, which is why you have to take it separately).For my formulation see ImmuneC.

- Consider supplementing Co-Q10 and certainly supplement carnitine, especially if you are over fifty, taking statins, following a ketogenic diet and/or dealing with any of the following: cardiovascular disease, cancer or cognitive decline. Aim for 30–120mg of Co-Q10 and 250mg–2g of carnitine, depending on your condition. For my formulation see CoQ Plus Carnitine.

- Consider supplementing chromium for better blood sugar and appetite control, and HCA to aid weight loss. You will need 200mcg of chromium up to three times a day if you are diabetic, and 750mg of HCA up to three times a day for weight loss. For my formulation see Cinnachrome.

HOLFORDirect offer a variety of supplements that help to maintain good cell health and optimal energy levels.

References

1. E. Cheraskin et al., ‘Daily vitamin consumption and fatigability’, Journal of the American Geriatrics Society (1976), vol 24(3):136–137.

2. W. Jubiz and M. Ramirez, ‘Effect of vitamin C on the absorption of levothyroxine in patients with hypothyroidism and gastritis’, Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism (2014), vol 99(6):e1031–e1034.

3. A. Vogiatzoglou et al., ‘Vitamin B12 status and rate of brain volume loss in community-dwelling elderly’, Neurology (2008), vol 71:826–832.2

4. E.J. Laird et al., ‘Voluntary fortification is ineffective to maintain the vitamin B12 and folate status of older Irish adults: evidence from the Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA)’, British Journal of Nutrition (2018), vol 120(1):111–120.

5. D.J.B. Marks, ‘Time to halt the overprescribing of protein pump inhibitors’

6. J. Rudd, ‘People taking heartburn drugs could have higher risk of death, study claims’, Guardian, 4 July 2017

7. S.J Euseen et al ‘Oral Cyanocobalamin Supplementation in Older People With Vitamin B12 Deficiency’ Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1167-1172

8. D.M. Mock, ‘Marginal biotin deficiency is teratogenic in mice and perhaps humans: a review of biotin deficiency during human pregnancy and effects of biotin deficiency on gene expression and enzyme activities in mouse dam and fetus’, Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry (2005), vol 16(7):435–437.

9. D.O. Kennedy et al., ‘Vitamins and psychological functioning: a mobile phone assessment of the effects of a B vitamin complex, vitamin C and minerals on cognitive performance and subjective mood and energy’, Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental (2011), vol 26 (4–5):338–347.

10. P. Langsjoen et al., ‘Treatment of statin adverse effects with supplemental coenzyme Q10 and statin drug discontinuation’, Biofactors (2005), vol 25(1–4):147–152.

11. K. Mizunoe et al., ‘Antifatigue effects of coenzyme Q10 during physical fatigue’, Nutrition (2008), vol 24(4):293–299.

12. K. Jones et al., ‘Coenzyme Q-10 and cardiovascular health’, Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine (2004), vol 10(1):22–30. See also: M. Dhanasekaran and J. Ren, ‘The emerging role of coenzyme Q-10 in aging, neurodegeneration, cardiovascular disease, cancer and diabetes mellitus’, Current Neurovascular Research (2005), vol 2(5):447–459.

13. M. Fukuda et al., ‘Carnitine deficiency: risk factors and incidence in children with epilepsy’, Brain Development (2015), vol 37(8):790–796.

14. J.P. Karl et al., ‘Military training elicits marked increases in plasma metabolomic signatures of energy metabolism, lipolysis, fatty acid oxidation, and ketogenesis’, Physiological Reports (2017), vol 5(17):e13407.

15. A.R. Lackey et al., ‘Evaulation of the utility of a dietary therapy second opinion clinic’, Journal of Child Neurology (2018), vol 33(4):290–296.

16. S.L. Pinkosky et al., ‘Targeting ATP-citrate lyase in hyperlipidemia and metabolic disorders’, Trends in Molecular Medicine (2017), vol 23(11):1047–1063.

17. N. Han et al., ‘(-)-Hydroxycitric acid nourishes protein synthesis via altering metabolic directions of amino acids in male rats’, Phytotherapy Research (2016), vol 30(8):1316–1329.

18. R. Sripradha and S.G. Magadi, ‘Efficacy of garcinia cambogia on body weight, inflammation and glucose tolerance in high fat fed male wistar rats’, Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research (2015), vol 9(2): BF01–BF04.

19. L. Schwartz et al., ‘Out of Warburg effect: an effective cancer treatment targeting the tumor specific metabolism and dysregulated pH’, Seminars in Cancer Biology (2017), vol 43:134–138.

20. I. Onakpoya et al, ‘The use of garcinia Extract (hydroxycitric acid) as a weight loss supplement: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials’, Journal of Obesity (2011), vol 2011:e509038.

21. H. Preuss et al., ‘An overview of the safety and efficacy of a novel, natural hydroxycitric acid extract (HCA-SX) for weight management’, Journal of Medicine (2004), vol 35(1–6):33–48.

22. L.O. Chuah et al., ‘In vitro and in vivo toxicity of garcinia or hydroxycitric acid: a review’, Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine (2012), vol 2012:e197920.

23. S. Davies, ‘Zinc, Nutrition & Health’, in J. Bland, 1984/5 Yearbook of Nutritional Medicine, Chicago: Keats, 1985.

24. S. Davies et al., ‘Age-related decreases in chromium levels in 51,665 hair, sweat and serum samples from 40,872 patients: implications for the prevention of cardiovascular disease and type II diabetes mellitus’, Metabolism (1997), vol 46(5):1–4.

25. Y.L. Chen et al., ‘The effect of chromium on inflammatory markers, 1st and 2nd phase insulin secretion in type 2 diabetes’, European Journal of Nutrition (2014), vol 53(1):127–133. See also: M.T. Drake et al., ‘Clinical review: risk factors for low bone mass-related fractures in men: a systematic review and meta-analysis’, Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism (2012), vol. 97(6): 1861–1870.

26. S. Anton, ‘Effects of chromium picolinate on food intake and satiety’, Diabetes Technology and Therapeutics (2008), vol 10(5):405–412.

27. K.A. Brownley et al., ‘Chromium supplementation for menstrual cycle-related mood symptoms’, Journal of Dietary Supplements (2013), vol 10(4):345–356.

28. J.R. Davidson et al., ‘Effectiveness of chromium in atypical depression: a placebo-controlled trial’, Biological Psychiatry (2003), vol 53(3):261–264. See also K.A. Brownley et al., ‘A double-blind, randomized pilot trial of chromium picolinate for binge eating disorder’, Journal of Psychosomatic Research (2013), vol 75(1):36–72.

29. N. Cheng et al., ‘Follow-up survey of people in China with type-2 diabetes consuming supplemental chromium’, Journal of Trace Elements in Experimental Medicine (1999), vol 12(2):55–60.

30. A.N. Paiva et al., ‘Beneficial effects of oral chromium picolinate supplementation onglycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomizedclinical study’, Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology (2015), vol 32:66–72.

31. N. Suksomboon et al., ‘Systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of chromium supplementation in diabetes’, Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics (2014), vol 39(3):292–306.

32. M.F McCarty, ‘The therapeutic potential of glucose tolerance factor’, Medical Hypotheses (1980), vol 6(11):1177–1189.

33. P. Holford et al., ‘The effects of a low glycemic load diet on weight loss and key health risk indicators’, Journal of Orthomolecular Medicine (2006), vol 21(2):71–78.

Comments

Join the Conversation on our Facebook Page