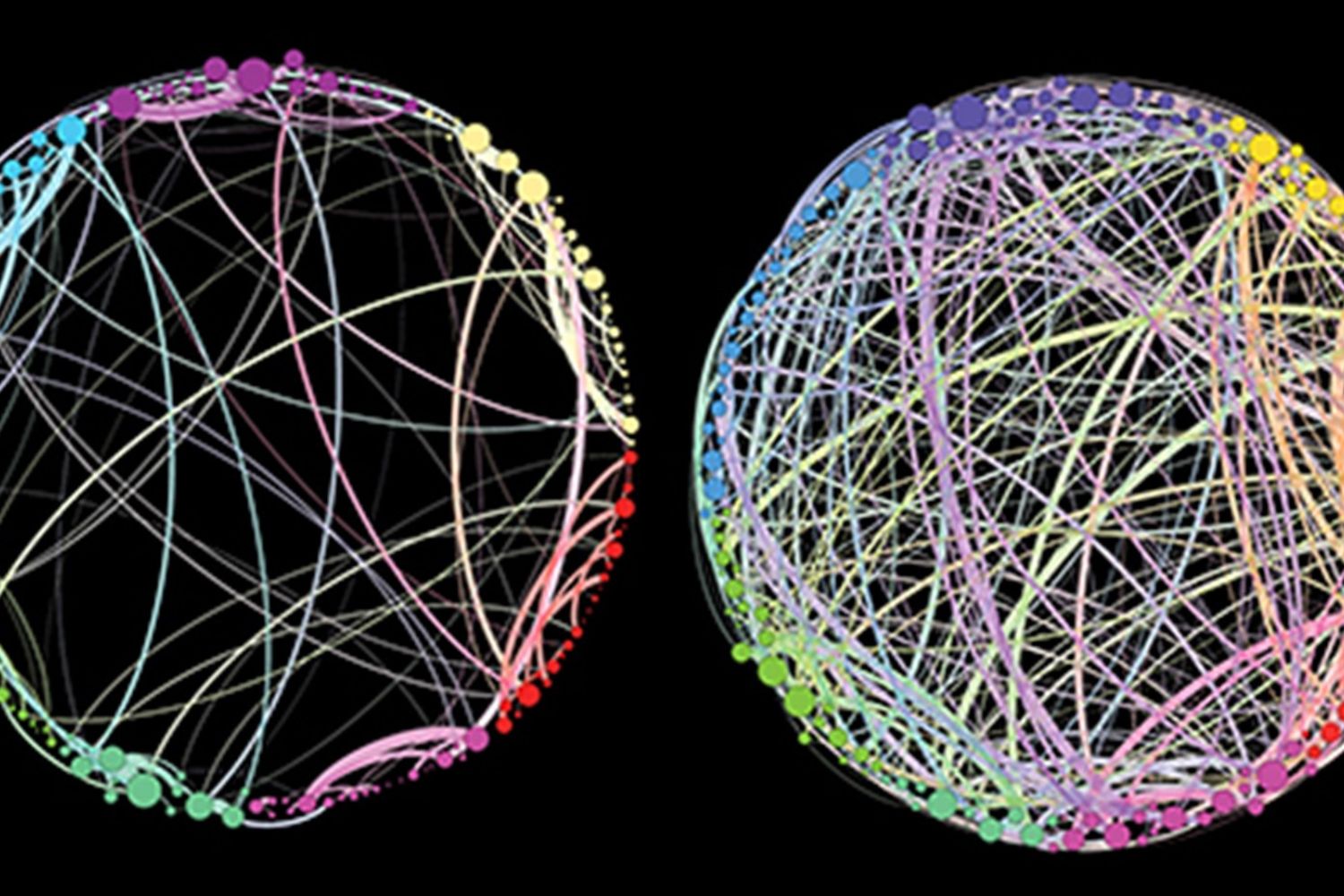

Left: Volunteer on placebo Right: Volunteer on psilocybin showing vastly more connections between different areas of the brain. © Used with permission of the Beckley/Imperial Research programme.

The ‘treatment’ involves giving a relatively high dose in a supportive environment with a guide/psychotherapist in attendance. There are several trials currently under way and what is being learnt about the brain on psychedelics is really interesting and unravelling some important new understanding on how brain function and our psychological experience interact. In fact, it was the original research into the workings of LSD, back in the 1940’s, that led to the idea that the brain’s chemistry could affect one’s mood, and the discovery of serotonin’s central role, an idea we now take for granted.

When Michael Pollan’s book ‘How to Change Your Mind – A History of Pyschedelics’ came out in 2018 it went to Number 1 in the New York Times bestseller list. Their review said “Gripping and surprising … Pollan makes losing your mind sound like the sanest thing a person could do”. It is an extremely well-written ‘travelogue’ of the scientists and ‘psychonauts’ that have pioneered this field of psychedelic research, intertwined with the author’s own psychedelic experiences as the guinea pig. It is certainly a good read and an extraordinary story about the pioneers, many of whom I have met and learned from, such as the late Dr Abram Hoffer, one of the first psychiatrists to explore psychedelics in mental illness and addiction. It was his research on B vitamins for the treatment of schizophrenia that got me started on my nutritional journey.

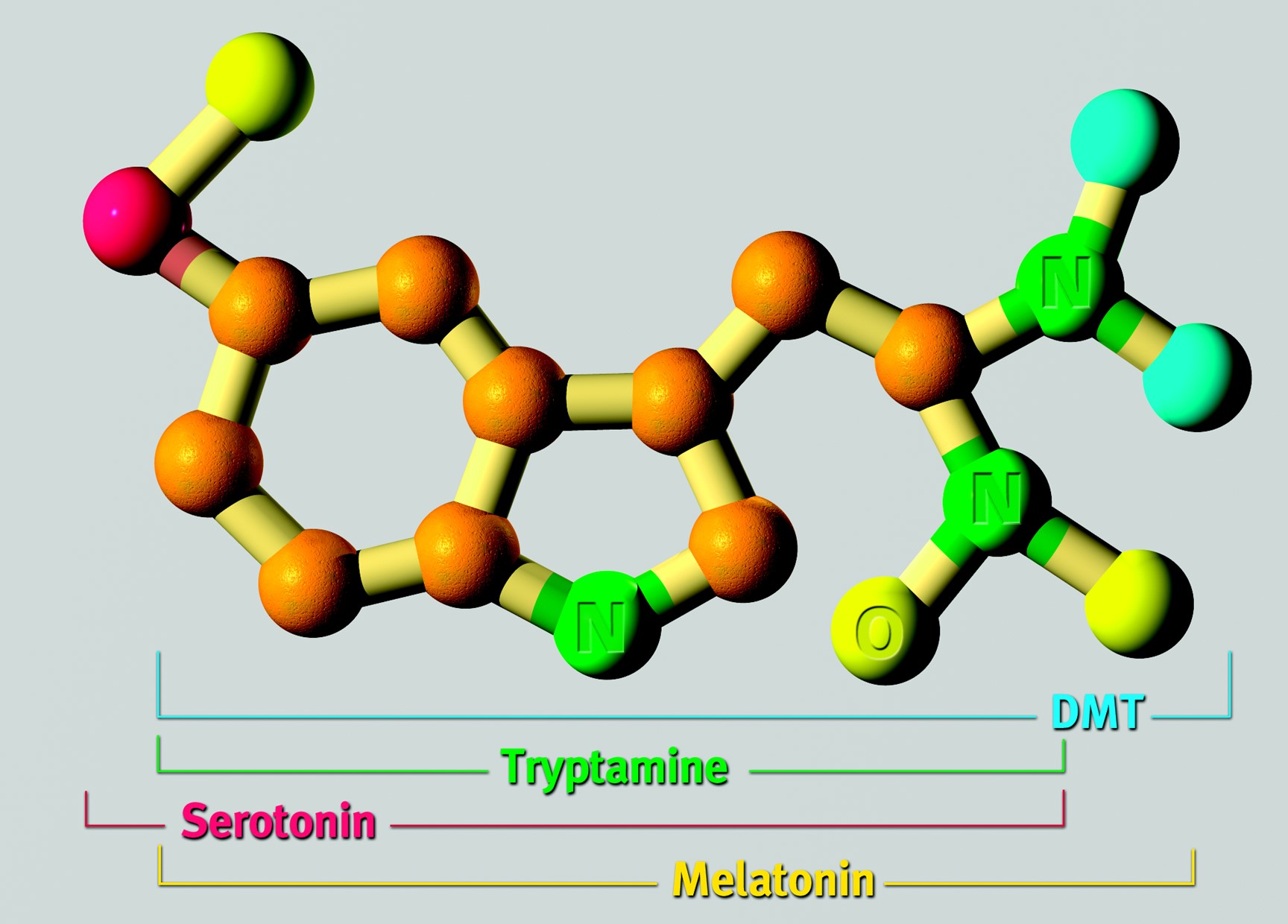

I’ve long been interested in these compounds and their role in our experience of connection and different status of consciousness. LSD and psilocybin are tryptamines, as is serotoninSerotonin is a hormone found naturally in the brain and digestive tract. It is often referred to as the ‘happy hormone’ as it influences mood…., melatonin and DMT (di-methyl-tryptamine), the only endogenous tryptamine that acts as a psychedelic. DMT is particularly concentrated in the pineal gland, considered by Descartes to be the seat of the soul. Research in this area is long overdue, having been shut down in the Vietnam era when young Americans would rather ‘drop acid than bombs’, thus leading to its illegalisation and a most unfortunate complete shut down on research.

The research door only started to open in 2006 when Roland Griffiths and Katherine Maclean at John Hopkins University School of Medicine in Maryland, risked their career and published a trial headed ‘Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences having substantial and sustained personal meaning and spiritual significance’. This well designed, placebo-controlled trial engaged the interest of the psychopharmacology community.

Fifty years on from the research shut down, some of the cutting-edge research involving the latest brain scanning techniques, has been done by the Beckley/Imperial Research Programme at Imperial College London, led by Robin Carhart-Harris, Professor David Nutt and Amanda Feilding. Nutt was the government’s chief advisor on drugs until he was fired after saying that, overall, alcohol was more dangerous that ecstasy (MDMA). Feilding began studying the mechanisms underlying the effects of psychedelics before their prohibition, and thereafter dedicated her life to reforming global drug policy, and reinitiating the scientific study of the substances.

What has been discovered is that these psychedelics have a major effect on a part of the brain’s circuitry called the ‘default mode network’. Discovered in 2001 the DMN, which consumes a lot of the brain’s energy, tries to keep everything in order. It is strongly linked to one’s sense of self, and possibly ego, and has been nicknamed the ‘me centre’ ‘orchestra conductor’ ‘the corporate executive’ ‘holding the whole system together’ in the words of neuroscientist Robin Carhart-Harris, chief researcher for the Beckley/Imperial Research Programme. It helps in the creation of mental constructs and projections, stringing together your story, which could include negative beliefs laid down from past early experiences such as “I’m not good enough”. The DMN keeps you focussed on yourself. It’s very useful for survival, but if over-controlling, the risk is you lose the sense of connection with others and the world at large. States of stress, depression, anxiety, compulsive-obsessive tendencies would fit in with an over-active DMN. (Schizophrenia is quite different and not the target of current research with psychedelics.)

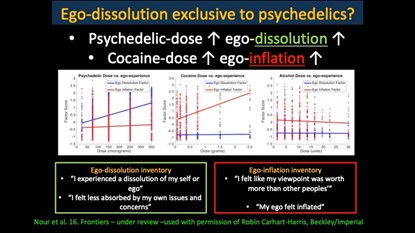

To provide a means for quantifying the psychological effects of different drugs Carhart-Harris developed a psychological scale of ‘ego-dissolution to ego-inflation’ with questioning volunteers “I experienced a dissolution of my self or ego” , “I felt less absorbed by my own issues and concerns” or conversely, “I felt like my viewpoint was worth more than other peoples” or “My ego felt inflated”.

He found that drugs such as cocaine are strongly linked to an increase in ego-inflation while the psychedelics had the reverse effect. Alcohol made no difference.

In his study of people taking psychedelics, the stronger a volunteer’s experience of ego-dissolution, the less active was the DMN during brain scans, with less blood brain flow and oxygen consumption in that region. In other regions of the brain, such as the limbic system which is involved with memory and emotions, including those traumatic experiences buried in our sub-conscious, activity increased. David Nutt describes the DMN as “the neural correlate of repression”. Dampening it down allows a fuller experience, not limited by the DMN’s narrowing aperture, but also the possibility of accessing memory of repressed traumatic events.

Broadly generalising, volunteers often have two stages of experience. One relates to part of a journey often going into, and somehow releasing or resolving or exposing but, in some way, ‘enlightening’ deep-rooted traumas. The other, usually occurring after this, is more like a mystical experience of union or connection or love. This breakdown between the strong boundary of ‘subject’ and ‘object’ is what the mystics call ‘non-duality’. It is this lack of connection that may lie at the root of much depression. I write about this in my book The Chemistry of Connection [link].

The effects on some people with treatment-resistant depression have been quite remarkable. In the first small pilot trial, published in the Lancet in 2016, involving twelve patients whose depression had not been relieved by any treatment – medication or psychotherapy – eight out of twelve patients were depression free one week after treatment, and five were still in remission 3 months later. These people had suffered an average of over 18 years of depression and had found no respite in any other treatment. A larger clinical trial is now underway.

Andrew, a 63-year-old materials scientist, was one of them. Andrew had suffered from untreatable depression for nearly two decades, arrived at Imperial College in London. He was led into a room with subdued lighting and smelling of incense, swallowed a pill and lay down on a couch covered with a colourful Mexican rug.

For the next seven hours he had an experience that was the most wonderful and the most terrifying of his life. ‘My ideas about the world swung through 180 degrees,’ says Andrew who lives in Shropshire. ‘At one point my mother, who had died some years ago, appeared as a demonic eagle. Later I experienced my ego dissolving. I became part of the universe but with no form. It was so beautiful.’

Three months later, Andrew’s intractable depression has been transformed. ‘It’s not gone but I have a different way of thinking about it,’ he says. ‘It is now a part of me but it no longer defines me.

‘I used to have nightmares and wake feeling certain the day would be bad and it was. Everything became felt flat and pointless. Now the bad dreams are fewer and they don’t trigger same despairing response. The depression is still there but it’s as though it’s in the next room. I’m off the antidepressants I took for 18 years.’

This fits in very well with research going on into the brain activity of meditators. Neuroscientist and psychiatrist Judson Brewer has been researching changes in brain activity at the Center for Mindfulness at the University of Massachusetts. He had found that the meditators dampened down activity of a part of the DMN called the posterior cingulate cortex. Brewer believes it is correlated with not so much our actual thoughts and feelings but ‘how we relate to thoughts and feelings.’ It is where we get ‘caught up in the push and pull of our experience’. The aim of the meditator is to become anchored in that field of awareness in which thoughts and feelings happen, and to allow them to pass. In other words, to develop detachment. But not a heartless detachment. Sending loving kindness to those who are suffering, as in prayer, is a meditation practice that reduces ‘me’ focus and increases connection to others. Brewer has found that these kind of states of mind/being are associated with less activity in the posterior cingulate cortex and, according to Carhart-Harris, less DMN activity.

One analogy is that we develop negative patterns of perception or behaviour based upon unresolved experiences creating the equivalent of grooves, like snow tracks, in our mind. These patterns get more and more hard-wired until it is difficult to see out of the box. It appears that psychedelics, taken in the right supportive context, can help to smooth out those grooves, or help develop more distance or perspective from those patterns of perception and behaviour. Some have likened it to a computer ‘reset’.

This approach is not a panacea. A small number report feeling worse. For those who benefit how long does that effect last? Is there a need for further sessions? These are all important questions.

MDMA (Ecstasy) assisted psychotherapy has also been shown to be effective for those with post-traumatic stress disorder, in randomised controlled trials.

Those experienced in psychedelic supported therapy emphasise both the need for an experienced psychotherapist or guide, and follow up with further sessions as opposed to the limited follow up in clinical trials.

Until psychedelics are reclassified for professional use in certain mental health conditions such follow-up is restricted by law. This is very much a new frontier.

Can Psychedelics Rebuild The Brain?

What is actually happening to the brain on psychedelics? While we don’t have a reset button as such, researchers at the University of California-Davis published a study [C. Ly et al., ‘Psychedelics Promote Structural and Functional Neural Plasticity’ Cell Reports 2018, 23(11):3170-3182] in June showing that psychedelics can actually increase the number of neuronal branches (dendrites), the density of small protrusions on these branches (dendritic spines), and the number of connections between neurons (synapses). These structural changes suggest that psychedelics may possibly be capable of repairing the circuits that are malfunctioning in mood and anxiety disorders.

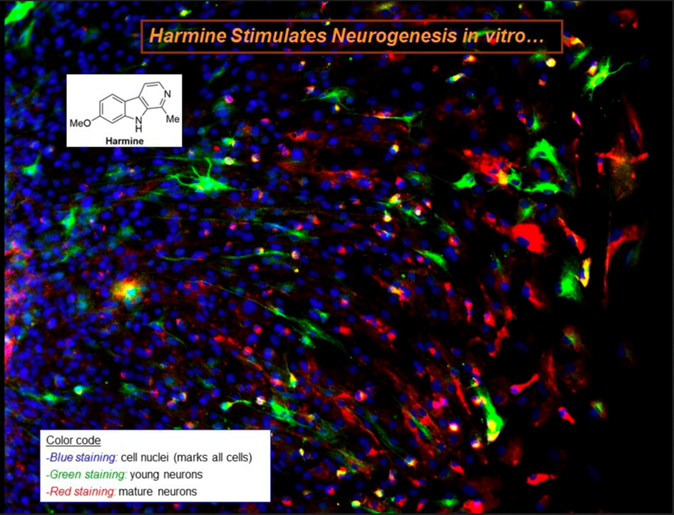

The psychedelic compound DMT is found in an Amazonian brew, Ayahuasca, made from a leaf and a vine. The leaf contains the DMT, and the vine contains the alkaloid harmine, which inhibits the breakdown of DMT, allowing it to be psychoactive. Dr Jordi Riba at the Sant Pau Institute of Biomedical Research, Barcelona, Spain has been researching the effects of Ayahuasca both on mood and its potential anti-depressant effects, and on neuronal development by exposing stem cells to the key chemicals found in Ayahuasca. He has reported that harmine stimulates the growth of new neurons. The hippocampus, a brain region associated with memory, does generate new neurons but, unfortunately, the rate of neurogenesis is not always sufficient to replace all of our damaged neurons as we age. Such brain shrinkage is the hallmark of dementia and other age-related cognitive deficiencies. It is far too early to say anything about whether Ayahuasca, or DMT which is produced in the brain, has a role to play in protecting memory, but anything that opens up the possibility of stimulating new neuronal development is worthy of scientific pursuit. The photograph below shows new neurons, in green, appearing after several days exposure to harmine.

© Used with Permission of the Beckley Foundation/Sant Pau Research Programme

Microdosing

In therapeutic use and clinical trials for mental illnesses relatively high doses are used. Psychiatrist Stan Grof, who has led some 4,000 LSD sessions with patients, uses 150 to 250mcg for therapeutic effect. There is, however, another use that is very much trending at the moment, especially in the California tech industry, which is microdosing usually between 5 and 20mcg – not enough to experience hallucinations but enough for a noticeable effect – on a more regular basis. Why do this? The Beckley Foundation, headed by Amanda Feilding, is currently researching this important question in a randomised controlled trial. For now the only evidence available are effectively surveys comparing those who do with those who don’t. The first study to be published, in the journal Psychopharmacology, reports higher scores on creativity, open and divergent thinking and lower scores on dysfunctional attitudes and negative emotionality, which is a precursor for mental illness. These are, of course, rather hard qualities to define and measure. The Beckley Foundation study also includes advanced brain scans and will also be the first to see what happens to the brain on microdoses of LSD. Could frequent low dose use of psychedelics be good for brain health and function? Studies indicate a therapeutic potential in depression.

This brave new world where neuroscience meets mysticism and deep psychology, using psychedelics as the microscope, has to be one of the most exciting fields in psychological medicine today, and not so far removed from the frontiers of nutritional research, such as that of methylationMethylation is what occurs when the body takes one substance and turns it into another, so that it can be detoxified and excreted from the…, which is so key to the formation of tryptamines, and dependent on B vitamins. (Faulty methylation, and lack of B vitamins, is associated with cognitive decline, as well as depression.) The natural anti-depressant S-Adenosyl Methionine (SAMe) is also used by the brain to produce the endogenous tryptamine DMT by adding on methyl groups to tryptamine (DMT is di-methyl-tryptamine), which is derived from 5-HTP and the essential amino acid tryptophan. My original formulation of Connect Food Formula was designed to provide all the precursor nutrients and co-factors to facilitate the brain’s production of endogenous tryptamines. It no longer provides 5-HTP, now in Mood Food Formula, together with other support nutrients. The Connect supplement instead supports healthy methylation.

This renaissance of research into tryptamine-based psychedelics is likely to reap rich rewards in our understanding of what goes wrong in the brains of those with mental illness and how to best promote mental health, and may soon become available for therapeutic use as the evidence grows.

Caveat: While psychedelics such as LSD and psilocybin are neither physiologically harmful or addictive, their positive effect is optimised by being taken in the right amount in the right circumstances with the right intention. I favour their legalisation for therapeutic use since that will also help make pure compounds available to health professionals to use to help people with mental health issues in the right set and setting. High dose usage in the wrong setting without appropriate support can be psychologically harmful.

Dig deeper:

Michael Pollan ‘How to Change Your Mind’, Penguin

Patrick Holford ‘Chemistry of Connection’, Hay House

Richard Miller ‘Psychedelic Medicine’, Park Street Press

My podcast with Amanda Fielding – What Can Psychedelics Teach Up About Mental Health.

See www.beckleyfoundation.org to support ongoing research

Comments

Join the Conversation on our Facebook Page