It’s estimated there are over 3.5 million vegans in the UK and growing, and probably at least as many vegetarians eating eggs and dairy products (lacto-ovo vegetarian), and many more who also eat fish (pescatarian) but not meat. Recent figures are hard to come by but it is highly likely that ten per cent of the UK population have turned away from meat largely as a reaction to the ruthless profiteering and cruelty of the meat industry, as well as obvious health benefits of going vegetarian, which is reflected in a steady decline in meat sales. A similar trend is occuring in other countries, notably the US. There is also the ecological argument that you can grow more food (proteinProteins are large molecules consisting of chains of amino acids. Proteins are essential nutrients for the human body – they are a building block of…) from a field of beans than a field of cattle, thus feeding more people, but I’m not going to go there in this article.

Vegetarians live longer and have less disease

Almost every survey on vegans, vegetarians and pescatarians show reduced risk for obesity, diabetes and heart disease, and their health statistics skew in the right direction including the key one – living longer. Two recent reviews of all the evidence classify vegetarians a third to half less likely to have diabetes than non-vegetarians1 and another shows less cardiovascular disease2. Another, in 2016, reported that people who eat more animal protein rather than vegetable protein have a greater risk for diabetes. This large study of over a hundred thousand people followed over several years, over 15,000 of which went on to develop diabetes. The higher their animal protein intake the greater was their risk of developing diabetes. For those in the top fifth for animal protein intake their risk went up by 13%. According to the researchers ‘substituting 5% of energy intake from vegetable protein for animal protein was associated with a 23% reduced risk of diabetes.’3

In terms of actual studies, the evidence is in the same direction. A small study of 49 diabetics either assigned to follow a low-fat vegan diet or a conventional diabetes diet (low fatThere are many different types of fats; polyunsaturated, monounsaturated, hydrogenated, saturated and trans fat. The body requires good fats (polyunsaturated and monounsaturated) in order to…, but not low carb, but with meat), both designed to be relatively low calorieCalories are a measure of the amount of energy in food. Knowing how many calories are in the food we eat allows us to balance…, found significant extra decrease in HbA1c, the best measure of long-term glucose control, and trends to less LDL and total cholesterol, but no difference in weight loss.

Some of the clearest research has been done on 7th Day Adventists. At Loma Linda University, Dr Gary Frazer has been studying 7th Day Adventists, who live much longer than most people. Most, but not all, are vegetarian. Comparing 7th Day Adentists who did eat meat to those who didn’t, his research showed that eating beef three times a week is associated with double the risk of heart disease a difference of 4-5 years life expectancy. In some studies vegans come out slightly ahead of lacto-ovo vegetarians (who have milk and eggs) and those who include fish but, in other studies, pescatarians do best. It seems than eating healthy plant-based diets confers many benefits, lower cholesterol, blood pressure, insulinInsulin is a hormone made by the pancreas. It is responsible for making the body’s cells absorb glucose (sugar) from the blood…., HbA1c and inflammation4. What’s not to like?

The Risks of Being Vegan

Well, there are risks, especially in more extreme vegan diets, and in those who know little about nutrition. The greatest risk is lack of vitamin B12, D, zincWhat it does: Component of over 200 enzymes in the body, essential for growth, important for healing, controls hormones, aids ability to cope with stress… and omega-3s. This is most concerning in pregnancy when these nutrients are vital to the developing foetus. Vegetarian women generally have lower zinc levels5. Vegans tend to have lower vitamin DWhat it does: Helps maintain strong and healthy bones by retaining calcium. Deficiency Signs: Joint pain or stiffness, backache, tooth decay, muscle cramps, hair loss…. and B12 levels6. Vegetarians and vegans tend to have lower omega-3 levels7. Another big danger with a less thoughtful vegan diet is that you end up with too much carbs. There’s a lot of processed vegan food that is high in sugar. Junk food is still junk food even if it’s labelled vegan. Vegan propaganda often downplays the well substantiated role in high carb, high GL diets promoting diabetes and Alzheimer’s. Whether vegan or not, eating a low GL diet is key as is getting enough protein. (See ‘Dirty Trick of the Month – What The Health?’ in the last newsletter issue.)

On the other side of the fence there’s quite an increase in people following low carb, ketogenic diets and thus usually eating more meat, often twice, sometimes three times a day. While this may have the effect of lowering both glucose and insulin levels dramatically is this OK as an ongoing lifestyle choice? Eating too much protein, especially from animal sources more than fish or vegetable sources, has some potentially serious downsides in relation to kidney function, cancer risk, insulin and accelerating ageing. But first, starting from the bottom up, how much protein do you actually need, regardless of source?

How Much Protein do You Need and How Much is Too Much?

Assuming good-quality protein, which means that the food contains the 8 essential amino acidsAmino acids are commonly known as the building blocks of protein. There are 20 standard amino acids from which almost all proteins are made. Nine…, 10 per cent of calorie intake, or around 35 grams of protein a day, is an optimal intake for most adults. 20 per cent, or 70 grams, is more than enough. I discussed protein needs more fully in Issue 101 last year. Vegetarians have less choice is terms of foods that have the right balance of amino acids – quinoa and soya are the best, followed by lentils and beans.

Above 80g a day, or 25% of calories over the long term starts to bad for you, especially if its meat protein. To put this into context a cooked breakfast, with sausage, eggs and bacon is about 40g of protein. The average portion of meat is 80 grams, about the size of a pack of cards. The average Brit eats 70 grams of red or processed meat a day, and that’s excluding white meat. Someone having meat, fish, eggs three times a day will certainly exceed 80g a day. A quarter of people in Britain eat 130g of meat a day – the equivalent of two portions of meat a day.The most popular low-carb Atkins diet, on average, recommends 80g two or three times a day, so that’s at least 160g, and sometimes as high as 240g per day. That’s the amount Michael Moseley put himself on for a month to see what it would do for a Horizon documentary programme. His cholesterol went up from 6.2 to 6.8 mmol/l (and mainly an increase in LDL) – that’s a 10% increase. His body fat went up by 3kilos, mainly in the trunk area (7lbs). That’s almost 2lb weight gain a week. His blood pressure went up 118/69 – 141/81. That’s about a 18.5% overall increase. All that in four weeks!

Now, he was eating bog standard meat, including processed meat – hamburgers, sausages and bacon. No fancy lean grass-fed beef.

All studies I’ve seen show that processed meat is much worse than red meat. According to Professor Walter Willett, from Harvard Medicial School large US based studies show that the risk of death and disease from eating processed meats are several times worse than other meats, both red and white, and that eating 35g a day of processed meat (eg a serving every other day), is associated with a 20% increased risk of premature death – mainly from cancer. The risk from processed meat starts to crank up with as little at 20g, half a serving, a day.

Now meat lovers and low carbers rightly point out there’s a world of difference between cheap processed meat products and real red meat, ideally grass fed. And also that Americans eat a lousy diet, with processed meat eaters more likely to be less food conscious, so there may be other differences in their diet skewing the association of processed meat and disease. But is that really the case for people who eat red meat, but not processed meat? I’m going to stick to looking at red meat. (There are no studies that I know of looking at the difference between standard red meat and grass-fed red meat.)

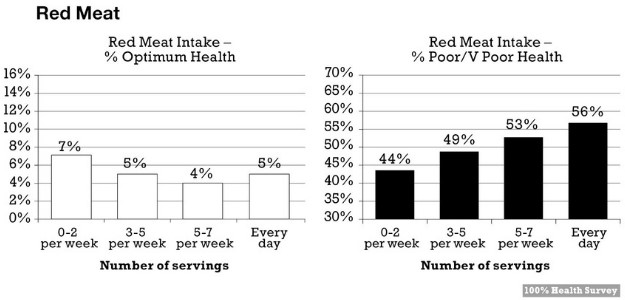

The very large European Prospective Investigation into Cancer (EPIC) study8 which followed half a million people, in 10 countries for more than 12 years, and found that moderate meat consumption did not correlate with lesser life expectancy. Only the risk from red meat above 80g a day, slightly increased risk of mortality, while 160g or more significantly increased risk. So, even for red meat, there is a warning about not having it so often.) White meat, eg chicken, made no difference. In fact it slightly reduced risk of premature death. Both a large trial in Journal of the American Medical Association9 and our own 100% Health survey on over 55,000 people, grades red meat as very slightly negative, while processed meat was right at the top of ‘bad’ foods being as big a risk factor as sugary drinks. In our survey (see below) those eating meat two or less times a week had the greatest chance of being in optimal health, and those eating meat every day had the greatest chance of being in poor health. This survey is free to 100% Health Club members.

Meat fans also point out that these small percentage increases mean even smaller numbers of people actually getting cancer, or dying younger, but it is undeniable that all the evidence points in the same direction of too much meat being bad for you.

What’s Wrong with Meat?

The more protein you eat the harder the kidneys have to work to eliminate the nitrogen waste products, or exhaust fumes of metabolizing protein. You certainly don’t want to go above 125g a day. A meta-analysis of 30 studies clearly shows measures of kidney function get worse at 25% of calories or more, which you would be eating with meat three times a day10. Poor kidney function is common in people with diabetes. The negative effect on kidneys seems to be mitigated by vegetarian protein, however excess too could be a problem, just harder to get there – you’d have to eat a lot of tofu, quinoa and beans.

But why is more meat protein potentially bad for you? One reason is its effects on raising insulin. Insulin-like Growth Factor (IGF-1) and insulin as something you want to keep low. The higher your IGF-1 and insulin the greater your cancer risk. High protein diets raise IGF-1. High refined carb and high protein would be the worst combination. IGF-1 also activates a vital ‘growth’ signaler called mTOR – and the more mTOR is activated the faster you age and the less well you repair because it switches off autophagy, a process that self-cleans damaged cells like an MOT, and the greater is your cancer risk. Virtually all cancers are associated with mTOR activation. So the higher your protein intake, especially from animal protein, the faster you age.

Another reason a high protein diet might put up your insulin is because it is acid forming. The more amino acids you eat the more acid load your body has to deal with. The body can ‘buffer’ short-term increases in acid load but consistently eating a high protein diet results in the over-production of metabolic acids which has been associated with the development which has been shown to impair peripheral insulin action and is associated with insulin resistance and worse blood sugar control, as well as a higher incidence of diabetes11. I discussed this acid/alkaline effect in Issue 101. Vegetable proteins, including beans and lentils, contain more of the alkaline minerals magnesiumWhat it does: Strengthens bones and teeth, promotes healthy muscles by helping them to relax, also important for PMS, important for heart muscles and nervous… and potassiumWhat it does: Enables nutrients to move in and waste products to move out of cells, promotes healthy nerves and muscles, maintains fluid balance in…, may be preferable in this regard.

However, foods such as these pulses also contain small amounts of carbs. More often than not they are shunned in low carb keto diets for this reason. Perhaps unfairly since the kind of carbs they contain are slow carbs. Thus beans, as an example are usually low GL.

Also, low carb diets that have more protein from vegetable sources do work well. An example of this was a study headed by Professor David Jenkins, who invented the Glycemic Index (GI), gave two groups of people a reduced calorie diet – one with a low amount of slow carbs (eg low GL), with high fat and protein, but from vegetable sources not meat; the other with higher carbohydrates, lower fat and protein12. Both groups lost nearly 9lbs (8.8lbs) in the four weeks, but those on the low-carb diet had greater reductions in their total cholesterol and LDL cholesterolLDL is short for low density lipoprotein. It is the “bad cholesterol” which collects in the walls of blood vessels, causing blockages. High LDL levels… levels. This diet was very close to my Low GL Diet.

Meat increases cancer risk

The greatest health risk associated with meat is cancer, especially colo-rectal. Any meat that is cured or made crispy by frying or roasting is introducing known carcinogens13. Also, too much protein is itself a growth promoter – and that includes cancer cells. Lower protein intakes are associated with reduced cancer incidence in those under age 65 and lower IGF-1 levels14. On the other hand, people 66 years and older, when more protein may be needed to conserve cells, higher protein intakes appear protective.

The fact is that higher protein dairy products and high animal protein diets can promote cancer cell growth through stimulating IGF-1 and mTOR. These are key growth signallers in the body – and if you’re growing you’re not repairing. The key to anti-ageing is repair and maintenance, not growth. So, a high meat and dairy ketogenic diet might be three steps forward two steps back. It’s very important not to overdo the animal protein.

There have been study after study showing that the more red and processed meat eaten the higher the incidence of cancer, especially colo-rectal cancer. More often than not there is no association with risk for white meat such as chicken, despite much of it being factory farmed. Haem ironWhat it does: As a component of red blood cells, iron transports oxygen and carbon dioxide to and from cells. Also vital for energy production…., the stuff in red blood, is itself a carcinogenic and that is much higher in red meat.

Bowel (colorectal) cancer is the second most prevalent cancer in the UK – each year more than 30,000 people are diagnosed with the disease, and around 18,000 die of it. Colon cancer is one the fastest growing cancers, especially in younger adults. A recent US study in the Journal of the American Medical Association shows a decline in colorectal cancer in those over the age of 50, an increase in younger people, and predicts a 50 per cent increase in incidence by 2020, and a doubling by 2030 in people aged 20–34 years old15. Colorectal is the third fastest growing cancer just behind breast and prostate cancer. To put this into context, in 2013 there were 143,000 diagnoses and 51,000 deaths in the US. If the cancer is detected in its early stages, there is an 85 per cent chance that it can be cured, but unfortunately many people are diagnosed too late. The correct diet and lifestyle is conservatively estimated to be able to reduce the incidence by 60 per cent.16

Although between 5 and 10 per cent of sufferers have a genetic predisposition to bowel cancer, there is no doubt that it is linked to diet and lifestyle. Carcinogens in what we eat, exacerbated by putrefying food (because of poor digestion and constipation), and microorganisms in an unhealthy gut, play a big part. The greatest risk factors are eating a diet high in animal fats, processed and red meat (especially grilled, barbecued or burnt), and low in fibreFibre is an important part of a balanced diet. There are two type of fibre; soluble and insoluble. Insoluble fibre helps your bowel to pass…, a history of polyps, smoking, excess alcohol, a lack of exercise, a lack of vegetables, a high calorie intake and prolonged stress. Grilling, burning and especially barbecuing meat, when the meat fat falls into the fire, produces known carcinogens called HCAs and PAHs, and processed and cured meat produce carcinogenic nitrosamines, a product of using nitrites in the curing process. Vitamin CWhat it does: Strengthens immune system – fights infections. Makes collagen, keeping bones, skin and joints firm and strong. Antioxidant, detoxifying pollutants and protecting against…, by the way, inhibits the formation of nitrosamines in the gut so taking vitamin C if you do eat cured meat such as bacon, might mitigate this risk. Haem iron, found in red meat not white, is also a carcinogen.

One of Britain’s top bowel experts, Roger Leicester, says ‘Bowel cancer is more likely to develop when people eat a lot of animal fat and there is slow-moving transit of food in the gut’. The combination of carcinogens from burnt animal fat – HCAs and PAHs – and processed and cured meat which produce carcinogenic nitrosamines, coupled with constipation is a recipe for colorectal cancer. An article in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition confirms this link17. According to both the World Cancer Research Fund and the American Institute of Cancer, the evidence of an association between red and processed meat and colorectal cancer is convincing. Professor Martin Wiseman, World Cancer Research Fund International’s Medical and Scientific Adviser says “The evidence on processed meat and cancer is clear-cut. The data show that no level of intake can confidently be associated with a lack of risk. Processed meats are often high in salt, which can also increase the risk of high blood pressure and cardiovascular disease.”18 Other researchers report the same association19. They recommend eating no more than moderate amounts of red meat and little, if any, processed meat. The World Health Organisation classify processed meats such as bacon, sausages and ham, as a carcinogen. Fish, on the other hand, is associated with reduced risk of various cancers and certainly no increase. However, fish and the essential fats they contain can also be damaged by burning or barbecuing.

There is a world of difference between organic, wild or fit animals and the meat most people are eating. Wild animals usually have considerably less than 5% of their bodyweight as fat while today, even most organic, free range chickens are closer to 20%. That’s because if you fed an animal more carbs, and restrict their exercise they get plumper faster and meat sells by the pound.

The Fibre Factor

One of the potential problems of a high meat diet, avoiding all grains and pulses, is getting enough fibre. Most of the fibre in vegetables breaks down on cooking. A high-fibre diet, especially soluble fibres found in oats and chia seeds, shortens the time food takes to pass through the digestive tract and thereby reduces carcinogen exposure. In other words, we can minimise our risk of developing colorectal cancer by choosing a diet high in fibre, which helps things move along more quickly, and low in meat, which takes longer to digest. You should be defacating with ease once if not twice a day. Few do, especially if on a low carb, high meat diet. Our own survey of 59,000 people found that only two in ten people (17%) have a satisfactory bowel movement every day, with 45% straining20. These two symptoms combined suggest that close to half the adult population suffer from some degree of constipation. These symptoms are more prevalent in men, which only one in 10 having a satisfactory bowel movement daily.

Fibre helps to reduce the ‘availability’ of carcinogenic compounds. Soluble fibre acts as fuel for the growth of friendly bacteria which, in turn, lower the pH (and therefore raise the acidity) of the colon. Higher acidity is associated with a lower risk of developing colorectal cancer.

One study examined the faecal pH of South Asian vegetarian pre-menopausal women compared with caucasian vegetarian and omnivorous women to see whether there was any link between this and their intakes of fibre, fat and cholesterol. The research found that there was indeed an association between high-fibre diets and faecal pH. It also showed that a vegetarian diet decreased the concentration of bile acids in faeces, a factor which has been linked to a lowered chance of developing colorectal cancer21. The vegetarians also went to the loo more often. Another study found that a high-fat, low-fibre, high refined-carbohydrate diet also increases activity of beta-glucuronidase, an enzyme secreted by toxic bacteria, which can generate carcinogens in the colon22. The activity of this enzyme can be measured in a stool test such as the Comprehensive Digestive Stool Analysis which a clinical nutritionist can arrange for you if you’re concerned.

Conclusion

My conclusion, purely from a health point of view, given that we need omega-3s, B12 iodine and seleniumWhat it does: Antioxidant properties help to protect against free radicals and carcinogens, reduces inflammation, stimulates immune system to fight infections, promotes a healthy heart,…, all of which are rich in fish, is that the healthiest diet probably involves eating fish three or more times a week and meat two or three times a week as a maximum to allow room for vegetable proteins from nuts, seeds, beans and greens. I don’t think it is possible to be optimally nourished and vegan without supplementing or eating fortified foods. I myself am a ‘smoked salmon vegan’ – I eat fish and eggs, generally avoid dairy products and meat. If I do eat meat, perhaps once a month, I make sure it’s from a truly free range and healthy animal that’s been well treated.

References

1. G. Fraser ‘Vegetarian diets and cardiovascular risk factors in black members of the Adventist Health Study’ Public Health Nutr.2015;18(3):537-545

2. Y.Lee and K. Park, ‘Adherence to a Vegetarian Diet and Diabetes Risk: A Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies’ Nutrients. 2017 Jun; 9(6): 603.; see also T. Chiu ‘Vegetarian diet, change in dietary patterns, and diabetes risk: a prospective Study’ Nutr Diabetes. 2018; 8: 12

3. Malik V et al., ‘Dietary Protein Intake and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes in US Men and Women‘. Am J Epidemiol. 2016 Apr 15;183(8):715-28

4. R.Najjar et al., ‘Defined, plant-based diet utilized in an outpatient cardiovascular clinic effectively treats hypercholesterolemia and hypertension and reduces medications’ Clin Cardiol. 2018 Mar;41(3):307-313

5. M. Foster et al ‘Zinc Status of Vegetarians during Pregnancy: A Systematic Review of Observational Studies and Meta-Analysis of Zinc Intake’ Nutrients. 2015 Jun; 7(6): 4512–4525.

6. A. Elorinne et al ‘Food and Nutrient Intake and Nutritional Status of Finnish Vegans and Non-Vegetarians.’ PLoS One. 2016 Feb 3;11(2):e0148235. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148235. eCollection 2016.

7. AA Welch et al ‘Dietary intake and status of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in a population of fish-eating and non-fish-eating meat-eaters, vegetarians, and vegans and the product-precursor ratio [corrected] of α-linolenic acid to long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids: results from the EPIC-Norfolk cohort‘, Am J Clin Nutr. 2010 Nov;92(5):1040-51. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29457. Epub 2010 Sep 22.

Also see B Sarter et al., ‘Blood docosahexaenoic acid and eicosapentaenoic acid in vegans: Associations with age and gender and effects of an algal-derived omega-3 fatty acid supplement’, Clin Nutr. 2015 Apr;34(2):212-8. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2014.03.003. Epub 2014 Mar 14.

8 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3599112/

9 R. Micha et al., ‘Association Between Dietary Factors and Mortality From Heart Disease, Stroke, and Type 2 Diabetes in the United States’ JAMA. 2017 Mar 7; 317(9): 912–924.

10 L Schwingshackl et al ‘Comparison of high vs. normal/low protein diets on renal function in subjects without chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis’ PLoS One. 2014 May 22;9(5):e97656.

11 L. Della Guardia et al., ‘Insulin Sensitivity and Glucose Homeostasis Can Be Influenced by Metabolic Acid Load.’ Nutrients. 2018 May 15;10(5)

12 G B Brinkworth et al, ‘Long-term effects of a very low-carbohydrate diet and a low-fat diet on mood and cognitive function‘, Archives of Internal Medicine, 2009, Vol 169(20): pp. 1873-1880

13 Abid, Z. et al., ‘Meat, dairy, and cancer’, Am J Clin Nutr, 2014 Jul;100 Suppl 1:386S-93S.

14 M. levine et al ‘Low Protein Intake is Associated with a Major Reduction in IGF-1, Cancer, and Overall Mortality in the 65 and Younger but Not Older Population’ Cell Metab. 2014 Mar 4; 19(3): 407–417.

15 C. Bailey et al., ‘Increasing disparities in the age-related incidences of colon and rectal cancers in the United States, 1975–2010’, JAMA Surg, 2015, Jan;150(1):17–22

16 M. Donaldson, ‘Nutrition and cancer: A review of the evidence for an anti-cancer diet’, 2004 Oct 20;3:19

17 Abid, Z. et al., ‘Meat, dairy, and cancer’, Am J Clin Nutr, 2014 Jul;100 Suppl 1:386S-93S.

18 https://www.wcrf.org/sites/default/files/Meat-Fish-and-Dairy-products.pdf

19 L Schwingshackl et al., ‘Food groups and risk of colorectal cancer.’ Int J Cancer. 2018 May 1;142(9):1748-1758

20 P. Holford, C.Trustram-Eve ‘100% Health’s Digestion Survey’, Holford & Associates 2017 – free download

21 S. Reddy et al., ‘Faecal pH, bile acid and sterol concentrations in premenopausal Indian and white vegetarian compared with white omnivores’, Br J Nutr, vol. 79, pp 495–500 (1998).

22 R. Hambly et al., ‘Effects of high- and low-risk diets on gut microflora-associated biomarkers of colon cancer in human flora associated rats’, Nutr Cancer, vol. 27 (3), pp 250–5 (1997).

Comments

Join the Conversation on our Facebook Page